Book pages 270-275

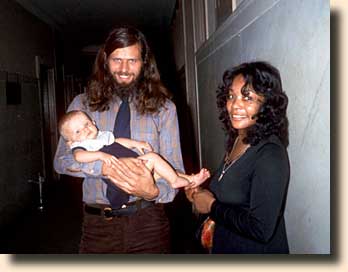

"There is no love like ghetto love." After four years of vagabonding in the

ghetto I ended up getting married to it. Annie is the only woman I recall

having taken an initiative with. As she was sitting there in a restaurant in

New York - irresistibly beautiful - it was evident from our first glances that

we needed each other. Both easy victims: she knew nobody, having just returned

from ten years of exile in England to attend her mother's funeral, and I was in

one of my depressed periods of vagabonding. We were both children of ministers

and had in different ways rebelled against our backgrounds. She was deeply

moved by my photos and wanted to help me publicize them. She had a strong

literary bent and a far greater intellectual breadth of view than I, so I soon

became very dependent on her to make the pieces in my puzzle fall into place.

Annie had to a large degree freed herself in her exile from the master-slave

mentality which makes marriage almost insupportable for those few unfortunate

Americans who fall in love athwart the realities of the closed system. For

"intermarriage" is indeed a subversive act. Even liberals grope for an answer

when the question comes: "Would you want your daughter to marry one'?" I

usually found common segregationists starting conversations with, "I don't care

whether people are white, black, purple, or green..." Ten sentences later they

would be sworn enemies of "intermarriage." Yet until it was prohibited in 1691,

there were plenty of intermarriages between white and black indentured

servants, and prior to the reduction of blacks to slavery the "poor white"

hatred of them was unknown. In most other countries, even post-slavery

countries like Cuba and Brazil, there is nothing resembling the fanaticism of

Americans towards intermarriage. Although I come from a conservative rural area

I cannot recall having heard a single negative remark in my childhood about the

frequent international marriages of Danes to African students. On the contrary

I sensed a strong solidarity and even envy towards those moving to distant

lands. But in America no interracial marriage can be viewed as simply a natural

union. In Hollywood, black promoters wanted to invest a lot of money to

publicize my slideshow, but first they wanted me to take out the section on my

wife: "It destroys your message, makes you look like just another liberal."

Many blacks and liberals will for the same reason fall away in this chapter. A

black woman was furious after seeing my slideshow with photos of several naked

black women (unaware as she was of my Danish culture in which nudity is highly

cultivated: family beaches and inner city parks are packed with nudes barely

minutes after the sun breaks through). "Aren't you aware of how irresponsible

you have been having had relationships with all these mentally unbalanced

women? Aren't you aware that slavery makes us all mentally ill?" She hit the

core question: How can I interfere as a neutral in a master-slave society

without becoming a part of the problem? And yet she made the same mistake as

most Americans of automatically assuming that a photo of a naked woman equals a

sexual relationship with her. She need not really worry, for unlike what I

found among black women in most of Africa, the black American woman has

developed enormous defense mechanisms against the white man in response to

centuries of abuse. Although I spent most of my time in black communities, more

than 90% of the women who invited me to share their beds were white. But the

suspicion of the white male sexual exploiter naturally always hung over me in

my journey. Walking at night in ghettos in the deep South young men would ask,

"Sir, you want me to get you a woman?"

I am fairly convinced that most women would not have offered me hospitality if

they had not sensed the non-aggressive component in me. Since I always saw my

vagabonding as a passive role and thus neither avoided nor initiated sexual

relations I think it is interesting to analyze what actually happened when I

came close to women. After a few days, if we got along well together, white

women would express sexual aggression. But even if we became intimate and

embraced each other, usually nothing more would happen with the black

underclass woman, especially in the South. It was as if something misfired in

us both - a shared acknowledgement that this was too big a historical abscess to

puncture. She could not avoid consciously or unconsciously signaling that this

was a relationship between a free and an unfree person, which immediately gave

me the feeling of being just another in the row of white sexual exploiters.

Most of my sexual and long-lasting relationships with black women were

therefore with women from the middle class or the West Indies who, although

more conservative than white and underclass women I met, had nevertheless freed

themselves from this slavery to a higher degree. Some Americans would say that

if you are aware that certain people live in slavery you should not as a

privileged white get yourself into such intimate situations where a sexual relationship or

"intermarriage" could arise. But slavery is a product of not associating with a

group completely freely as equals, thereby isolating and crippling it.

Annie was one of my exceptions with the underclass. For although her surface

seemed very "middle class" after her long leave, she was in her fundamental

outlook marked by her underclass upbringing. Such a relationship could

probably have worked with much trust and effort by both partners, but because

of my racism, sexism, and above all that unseeing "innocence" which will always

be the ultimate privilege of the ruling class, this wasn't what happened.

Instead it became such a painful crushing defeat for me that I for instance

couldn't reconcile it with my original book. Even the beginning went wrong. We

got married Friday the 13th of September, with no place to live.

our wedding ceremony in city hall since the maid had to

make a phone call about being late back in the consulate.

A maid let us spend our honeymoon in the luxury apartment of the South African consul who had been called home by his apartheid regime. Afterwards we ended up in the worst area of the ghetto. We had hardly paid the first month's rent before all Annie's savings were stolen. We lived on the fifth floor of a building with only prostitutes, destitutes, addicts and welfare mothers. Annie had not lived in underclass culture since her childhood and it was a terrible shock for her to end up here. Due to her looks and the place we lived she was constantly "hit on" by pimps and hustlers, who tried to recruit her. When I had to hitchhike away for some days Annie was kidnapped by a prostitution ring who forced her at gun point to strip naked while they played Russian roulette with her "to break her in." At night she managed to flee through a bathroom window without clothes out into the city streets. When I came home she was lying dissolved in tears and pain. The attacks of the pimps continued, and it didn't help matters that I was white. One day a pimp scornfully threw a handful of money at Annie on the bus. With my old vagabond habits I picked it up. Annie was furious with me and wouldn't talk to me for a week. There were violence and screams and frantic pain in the building day and night. Several times in the beginning I tried to intervene between pimps and the ho's they were beating. There was also a pyromaniac. Almost every night during the first months we were woken up by the fire alarm and saw flames burst out from the adjoining apartments. We were so prepared that we had everything packed all the time. The first thing I would grab was a suitcase with all the thousands of slides for this book. One night when we were all standing half-naked in nightclothes on the street I asked Annie to keep an eye on the suitcase while I photographed the fire, but she didn't hear me in the noise and when we got back to the apartment. it had been left behind. I rushed down to the street and found the suitcase still standing there. Everyone in the building called it a true miracle as nobody had ever seen any valuables left on the street for even one minute without being snatched.

The psychological pressure was at first worse on Annie than on me. We tried to

get welfare in order to move, but got only $7. Almost every night she lay in

tears and despair. In the first months when I still had some psychic surplus

left I tried to penetrate into the world which had so evidently disintegrated

for her. Like most of my other relationships in America, this one was due to

violence. We had met each other as a result of the murder of her mother; and a

few months afterward her stepfather was found staggering down the street

mortally wounded by a knife. A horrifying pattern from her childhood began to

appear for me in these tear-filled nights. When her 16-year-old mother had given

birth to her and a twin sister it was seen as such a sin in the minister's

family that the mother had been sent up North and Annie down to an aunt in

Biloxi, Mississippi. All Annie recalls from these first four years was the

drunken aunt always lying in her shack, while Annie sat alone outside in the

sand. One day she almost choked to death on a chicken bone and struggled

desperate and alone. Nobody came to help her. The grandparents discovered the

neglect and took her back to Philadelphia, Mississippi, where she received a

rigorous fundamentalist upbringing. All display of joy, dance, and play was

punished. Often she was hung by leather straps around her wrists in the

outhouse and whipped to a jelly. On the way home from school there was almost

daily rock-throwing between the black and the white kids. One day the white

kids turned German shepherds on them and Annie was severely bitten. Two of these white children

later joined the Ku Klux Klan, and one of them, Jim Bailey from Annie's street,

was the one who later murdered three civil rights workers in 1964.

After this

Klan violence, with parades of burning crosses through Annie's street, she fled

up North and later went into exile. Since she was the first black to integrate

the town's library, she never dared to return. The more these tearful nights

revealed, the more shocked I was. She was incredibly sensitive and one night I

recall her crying at the thought of "the white conspiracy" which had kept her

and the other black school kids ignorant about the murder of six million Jews.

Finally Annie managed to get a temporary office job in the Bureau of

Architecture where she took care of bills from construction companies. She

caused great turmoil by discovering one swindle and fraud after another. With

her unusual flypaper memory she could detect how the construction companies had

months before sent bills for the same job but in different wording. For years

these Mafiosi had ripped off the city. Every day she came home and told me

about how she had just saved the city $90,000 or the like. When her job ended,

her boss told her she could write any recommendation she desired: he would sign

it. But we ourselves still had no money and it was as if this corrupt

atmosphere helped to further break down our morale. When the rich steal, why

shouldn't we? When we one day found a purse with $80 in it in the hallway, it

took us a long time to decide to give it back to the owner a welfare mother.

When she opened her door she grabbed the purse without a word, with a

contemptuous look as if to say, "You must be fools, trying to be better than

others here." From that moment everything slipped more and more in a criminal

direction. It had been our idea that I should use the time to write a book.

Annie and others felt that I ought to write about my ghetto experiences with

the eyes of a foreigner. In the beginning I sat day after day in front of a

blank sheet of paper, but it was impossible for me to get a word down in that

violent and nerve-wracking atmosphere.

Gradually we both lost our self-confidence and I gave up. The less surplus we

had, the less hope, the more violent did the atmosphere become between us.

Little by little Annie started to drink in response to my increasing

insensitivity. She began to nag me for being nothing but a naive liberal.

These endless nights are more than anything the reason for attacks on liberals

(or myself) in this book. For the first time in my journey I began to lose

faith in blacks - to look at their actuality rather than potential. I was

becoming Americanized, had become a victim of the master-slave mentality. The

more I lost faith in people (and my own future), the more I seethed with hatred

and anger. To avoid the unendurable atmosphere with Annie, I began to spend

most of my time on the street. The more powerless I became, the more dismal my

prospect, the more she lost faith in me. One night she shouted, "You can't even

provide! You hear, blue-eyed nigger, provide!" What was even worse was that

although I constantly tried to get work I started blaming myself. I did nothing

but stand in line. In the mornings I sat and lay in line in the blood bank to

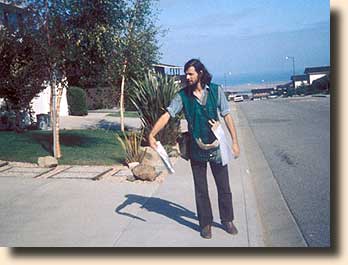

get $5. Every day at 11:00 for eight months I stood in an hour-long soup line

and at night I would often eat in a church. The rest of the day I would stand

in line to get work, which was impossible as l had no skills. If I got there at

four in the morning I sometimes succeeded in being hired for a day to throw

advertisements in the affluent suburbs for $2 an hour.

After a while I gave up and spent more and more time with the criminals in the street. I was never involved in any large-scale criminal activity, but it was clearly moving in that direction. One night when a guy was telling me shakenly that his brother had just been murdered in Chicago I just replied coldly, "What caliber pistol?" Only afterwards did it dawn on me how deep I had slipped down. During the time I lived with Annie eight people had been murdered on our block, some of them acquaintances. Theresa, who had so often given me free food in her coffee shop, was murdered one day by a customer who couldn't pay his bill of $1.41. Sometimes even the walls in our hallway were smeared with blood. When I came home late at night Annie would often be lying in a fog of tears and booze. I hardly cared any more. In the end for fear of the destructive quarrels I would not come home until she was asleep. Our sex life, like everything else, disintegrated.

Finally I harbored such hatred for both blacks and whites around me that I

became afraid of myself. One night when Annie had been drinking I became so

desperate that I aimed a blow at her in the darkness. The next morning she had

a black eye like everyone else in the building had had. Having never before

laid a hand on a person, I was shaken. I had a sudden fear that I would end up

killing her one day. The only way I could break the ghettoization was flight.

We managed to get a tiny room for Annie in a white home outside the ghetto.

After that I went straight for the highway. The highway I knew meant security

and safety, recreation and freedom. For four years I had lived an escapist

privileged vagabond life in ghettos without being affected. When I became a

part of the ghetto, I was destroyed in less than a year, had ended up hating

blacks, had lost faith in everything, and had seen the worst parts of my

character begin to control my behavior. One of these was an increasing

selfishness and aggressive callousness in my relationship to women. It was no

coincidence that I immediately entered a period of conspicuous consumption of

"girls" with my friend Tony in North Carolina. I had no inhibitions left. And

yet I was not exactly a horn seducer. Time and again Tony whispered to me,

"Hey, why don't you make a move?" and time and again he ended up having to

drive my date home prematurely. And then every night there were disturbing

obstacles. One night I couldn't get home with my date because of a shootout in

the street. Another night we all went to see Earth, Wind and Fire in Chapel

Hill and I used my white privilege to "con" my way in for free as I never had

money. This so irritated Bob, who drove the car, that on the way home he

suddenly stopped and said, "Hey, man, you gotta get out, understand?" Since Bob

was a double murderer, having killed both his wife and her lover, and everybody

knew he boiled inside, nobody tried to intervene and I had to get out in the

frosty night in the middle of nowhere.

An essential tool in dating is the car. Since I couldn't take my dates for a

ride I instead invited them for what I loved most of all in the world:

hitchhiking. It was these trips more than anything else which made me aware of

my sex-ploitative frame of mind. I had lived with blacks so often that I paid

hardly any heed to being "on the wrong side of the tracks," but to hitchhike

with a black woman quickly shakes one into "place" again, especially if one is

as ignorant as I had managed to remain about the additional master-slave

relationship of men to women. Because of my vagabond attitude that the driver

should be "entertained," if the driver was a woman or a gay man, I would sit in

front to make conversation, whereas if it was a straight man I would make the

woman sit next to him, even if she didn't want to. The reactions from the white

male drivers were terrifying. If they didn't content themselves with

psychological torture of the women, they would use direct physical

encroachment. Although most of those I hitchhiked with were well-dressed

daughters of professors and doctors in the North and had the education and

trust in their surroundings which made them - unlike ghetto women - even dare

to go on such a trip with a white, they were considered as nothing but easy

sexual prey or even whores. Several times lustful drivers violently tried to

push me out. For some of these women it was their first chance to see their country. Most didn't even last to the

state line. One lasted 4,000 miles through Canada and the Grand Canyon - then

broke down in a hysterical fit which almost had us both arrested. I was still

enormously out of balance after my ghettoization and I decided I needed to

recreate myself in a calm family atmosphere. After having lived in a couple of

white homes I searched back to the most harmonious and stable married couple I

could recall having seen in the underclass: Leon and Cheryl in Augusta,

Georgia. Their love and devotion to each other had been so enriching and

contagious that I often thought of them in the course of my own abortive ghetto

love as living proof to myself that real ghetto love could thrive. While I had

lived in their home I had had peace and support, enabling me day after day to

hitchhike out to explore the poverty in the area. But when I came to their

house I immediately felt something had changed. Leon asked me in, but he was

not happy. He seemed to be in a trance as he told me his wife had died from a

disease which was curable but which they had not had money to get under proper

treatment before it was too late. Leon had not recovered from the loss. He

never went out of his house which stood right next to the elite medical school

in Augusta. All day long he sat on the blue shag carpet in front of his little

stereo as if it were an altar, listening to music while staring at a photo of

Cheryl above. Some days he sang love songs throughout the day, putting her name

in them. Once in a while he would scream out in the room: "I want you! I want

to hold you. I want to be with you again ... We must unite, be one... I want to

die... die... " Never have I seen a man's love for a woman so intense. At most

once a day would he turn around and communicate with me, and then only to tell

me about how he wanted to join Cheryl in heaven. Sometimes when he stared

directly at me with this empty look as if I were not there my eyes would fill

with tears. I felt a deep understanding for him, yet couldn't express it. In

the evenings he lay in his room. His mother or another woman would bring us

cooked food in the two weeks I stayed there. This depressing experience made me

look deeper into myself. I became determined to go back to Annie, and later she

returned with me to Denmark. Our relationship had suffered too much, so after

a while we separated. We achieved a good working relationship and she helped

translate parts of this book and all of the film.

grandmother who died shortly after.

Three years later I traveled all over America to give or show this book to all

those friends who made it possible. One of them was naturally Leon, who had

helped me so much and was one of those I had in mind to come and help run the

show in Europe. But when I came to his screen door with the book under my arm,

a strange woman answered my knock. No, Leon didn't live there any more. He was

shot three years ago - by a white man. All afternoon his mother showed me the

photo album with Leon and Cheryl's pictures and told me tearfully about their

three happy years together. We sat sobbing in each other's arms on the front

porch. I know that Leon and Cheryl are united again. "There is no love like

ghetto love."

Letter to American friend

Copyright © 2005 AMERICAN PICTURES; All rights reserved.