|

|

Jacob Holdt’s American

Pictures:

A Note on Style in Poor Cinema

J. Ronald Green

Who says

that fictions only and false hair

Become a verse? Is there in truth no beauty?

– George

Herbert, Jordan

(I),

c. 1633

In connection with its recent (Apr 21-Oct 31,

2021) one-person show of the work of Black American filmmaker,

Arthur Jafa, the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, north of

Copenhagen, sponsored a conversation between Jafa and Danish

photographer and filmmaker Jacob Holdt. To open the discussion, Jafa

said to Holdt: “I grew up in Clarksdale, Mississippi, in the middle

of the Delta. I love William Eggleston’s work quite a bit. And it’s

obviously very great work as political photography. But I always

felt like there’s a wall of aestheticism between what it is he takes

pictures of and the work itself. And that’s not a critique, that’s

just a part of his work. But I just had never seen images of the

South before I saw your pictures, outside of my family’s photo

albums – that would be like the only equivalent of it. If I had to

put one question to you it would be how did you get these pictures?

How did you manage the level of intimacy or access?” Holdt responded

that “an important answer to your question is to travel with no

money.”

This essay is a heuristic exploration of a

cinema of poverty. Holdt’s

film – composed of still photos, intertitles, and sound – represents

a life-long, in-person testimonial of American poverty and racism.

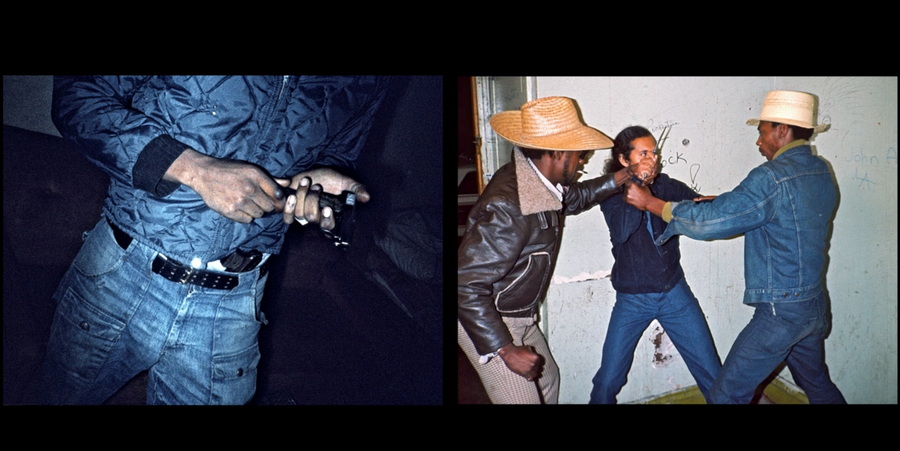

Holdt deploys familiar attractions such as spectacle, sex

and violence,

and celebrity to

dramatise his portrayal of American inequities. I would expect

viewers of American

Pictures to

relate, as I did, and as Jafa did, to the life-long, life-risking

breadth and depth of this outsider filmmaker’s picture of the USA.

That picture, produced in the 1970s and ‘80s, is as relevant today

as it was then; in fact, Holdt – in response to the Black Lives

Matter movement – is currently updating the book that he produced

from the slide show and film—the working title of the updated book

is “Roots of Oppression”. My

own book discusses details of the original film version of American

Pictures,

including content, methods, critical targets, and issues. It

analyses those details in the light of the film’s effectiveness and

critical integrity, particularly in relation to money. The analysis

sometimes compares richer cinemas to Holdt’s film, but the focus

remains on poor cinema. A companion book manuscript focusing on rich

cinema also exists, in draft. This analysis of poor cinema grew out

of my two books on Black filmmaker, Oscar Micheaux, where I argued

for a middle-class cinema, an idea supported by analysis of the

content and style of all Micheaux’s extant films.

The idea of

“poor cinema” is discussed in the last two chapters of the

poor-cinema book manuscript, and will not be dwelt on in this essay,

except to say that the idea is related to prior formulations in the

film-studies canon such as Julio Garcia Espinosa’s essay, “For an

Imperfect Cinema,” and Fernando Solanos and Octavio Getino’s

manifesto, “Toward a Third Cinema,” as well as the film movements of

Third Cinema and Tricontinentalism discussed in the edited

collections Questions

of Third Cinema and “Rethinking”

Third Cinema.

More recently, the poor-cinema idea has been briefly summarised and

re-theorised by Hito Steyerl in The

Wretched of the Screen.

The above

exchange between Jafa and Holdt about the origins of Holdt’s

intimate, authentic pictures of Black American life, was primarily

concerned with the content of

Holdt’s pictures. Most of my book on American

Pictures also

deals with content and its relation to money. But the same poverty

that conditions Holdt’s content, may also affect his aesthetics,

which is another of Jafa’s and Holdt’s concerns. A close look at

Holdt’s film suggests how a “poor” style – analogous to Oscar

Micheaux’s style in racist 1920s and ‘30s America – can have a

discoverable aesthetic, a style unique to its material condition.

Below I

analyse instances of Holdt’s outsider style using detailed analyses

of shooting, editing, and mise-en-scène in order to show how style

may relate to money, and to show how a better-capitalised film style

might structurally lack the same interest, authority, and

effectiveness as Holdt’s under-capitalised project.

The Shot

A close

analysis of certain elements of Holdt’s shots results in

quantitative information such as the following:

Shot

Distance

|

Extreme Long Shot |

0% |

|

Long Shot |

60% |

|

Medium Shot |

32% |

|

Close Shot |

7% |

|

Extreme Close Shot |

0% |

Shot

Angle

|

Straight On/Perpendicular/90-Degree |

20% |

|

Oblique Side |

53% |

|

Acutely Oblique (hereafter “Acute”) Side |

27% |

|

Oblique High |

38% |

|

Acutely Oblique (hereafter “Acute”) High |

9% |

|

Oblique Low |

4% |

|

Acutely Oblique (hereafter “Acute”) Low |

0% |

|

Rear |

4% |

|

Extreme/Dutch/Tilted Horizon |

0% |

This simple analysis describes a shooting

style. It

would be rash to generalise too much from abstract figures such as

these. In order to know the aesthetic effect of such a high

percentage of long shots and medium shots; of the almost-complete

absence of extreme distance, extreme closeness, and extreme angle;

of the low but still-substantial incidence of close distance; and of

the very high percentage of oblique angles, one would need to select

some specific examples and see how those shot characteristics work

to produce beauty, effect, and meaning.

The

following, for example, is a very typical shot that I would classify

as an oblique side-angle, oblique high-angle, long shot,

statistically the most common type of shot among the analysed shot

characteristics in Holdt’s film.

The side and high angles

are oblique and thus less photographically expressive or expressionistic than a

shot set at an acute angle from the subject matter. This leaves the content of

the image to speak for itself more than it would be able to do if the

photographic medium were insisting on its expressive prerogatives. The

conjunction of the high and side angles lend the objects a degree of dynamic

potential, owing to tensions set up in relation to the force of gravity, and by

the complex, almost cubistic lines of graphic force nested within the 90-degree

rectilinear frame. The unbalanced, cubistic qualities stimulate the eye and

brain, which aestheticises the image, rendering it recognisable within a canon

of social documentary image making, much of which could be categorised as, in my

terms, “poor” photography and cinema, a tradition that extends from, say, Lewis

Hine to the Film and Photo League and beyond – in that sense, nothing new.

The dominant effect of those oblique angles is

to present an account of the photographer’s experience of the

represented situation, suggesting an attempt to be faithful to the

effect of the observable surroundings in the picture. Thus, the

aestheticising dynamics and cubism of the shot result simply from

the photographer’s wish to get all the graphically rich, but also

crushingly decrepit, clutter on both walls and on the tabletop into

a single shot, and by doing so, to communicate his perception of

this woman’s over-determined situation. Holdt’s stylistic choice –

to shift angles slightly, rather than considerably – renders the

situation faithfully; at the same time it strengthens a Kantian

sublimity inherent in the condensed clutter, the byzantine

corruption of the represented life world, all this rendered

slightly, but unnervingly, unstable by the tilted camera angles. The

content shows the uncountable evidences of a general textural

fragility; the style shows the potential for collapse.

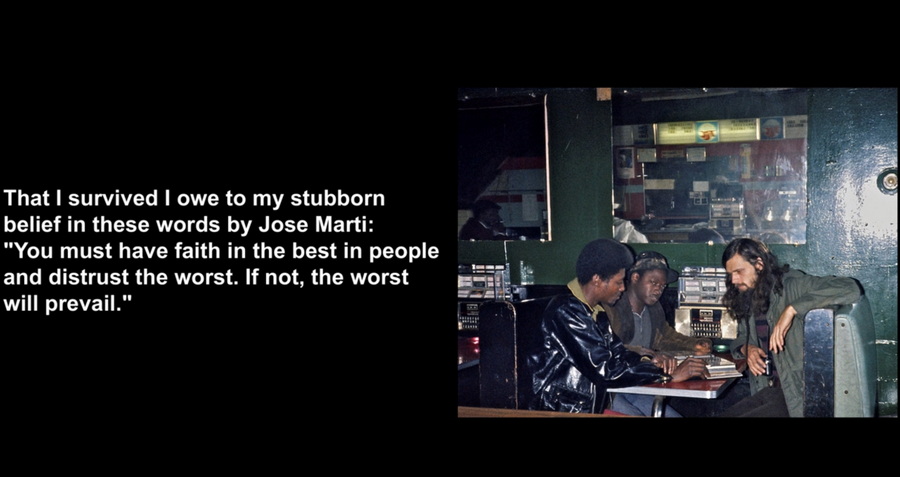

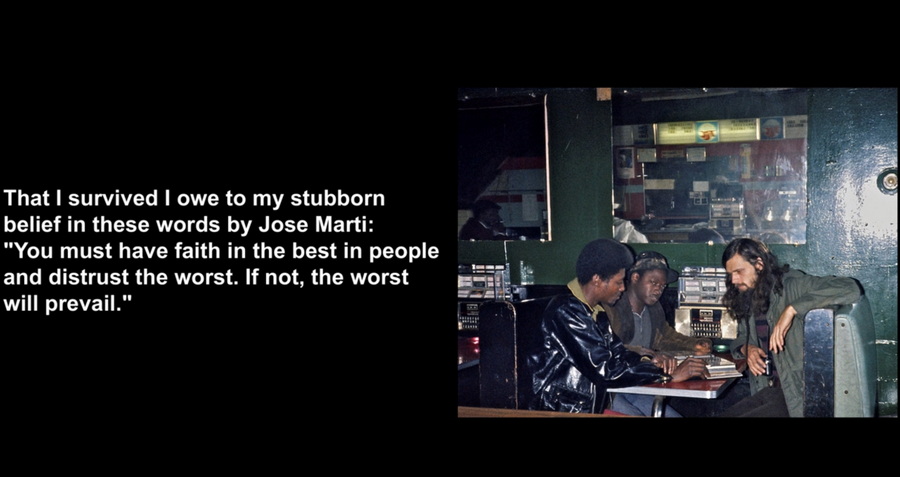

Moving

closer in another environment, the scene below is a typical oblique

side-angle (almost straight-on angle) medium shot.

In this

case, the aesthetic arrangement seems dominated by the balancing of

graphic line and mass, and the isolated weights of colour. A massing

of graphic incident and colour-density on the right quarter of the

picture is balanced by the brown slab of veneer on the left frame

line, by the very stable, three-dimensionally bottom-heavy, blue

triangle of the man’s sweater, and by the photographer’s beer can

anchoring the lower-left corner of the composition. The strong

graphic line running from the woman’s legs through her elbow and

face is balanced by an equally weighty line running from the

lower-left-corner beer can across the couple’s two heads, producing

a triangle of graphic forces, which is offset a few degrees from the

vanishing point that is located somewhere to screen-right of the

woman’s left shoulder.

That

triangular crossing of massive lines supports the subjects’ worn and

weathered heads, and cradles those heads in a graphically – and

emotionally – complex nexus of graphic forces. For example, another

line runs from the same lower-left beer can across the man’s right

elbow and forearm to his invisible but strongly implied left hand,

which crosses behind, and presumably holds onto, the woman’s waist.

The added triangulation adds strut-like stability to the dominant

triangular mass converging at the two heads. The man’s unseen but

inferable embrace of the woman also conveys ambiguous emotional

strength to the zone of the picture where the graphic forces are

gathered. The prominent graphic lines of depth created “naturally”

by the optics of the lens also come into play, creating another

system of triangulations at the acme of the vanishing point, this

time adding third-dimensional weight to the arrangement.

The effect of a converging of two-dimensional

and three-dimensional graphic forms near a single point is further

strengthened by a more subtle graphic line – suggested primarily by

the fragmented, but nonetheless strong, line of white dots on the

juke box to the right. That bright, rigid broken line is faintly

mirrored by a lighter line of white dots on the wall to the left of

the man’s head. That line crosses the woman’s eyes. There is a

punctum near

that crowded crossroads that is located in the glance of the woman

straight at the camera and the viewer. Her direct glance projects in

the exact opposite direction from the graphic lines of depth created

“naturally” by the optics of the lens. Her glance at us reverses

perspective and forcefully breaks the fourth wall of the picture’s

implied space. The strut-like triangular form resulting from the two

lines of force emanating from the lower-left beer can adds another

slight cubistic effect, suggesting a counter-intuitive vanishing, or

emanating, point at that beer can, an apex to a triangle. Since that

apex is in the third dimension, it helps pop the couple’s heads and

upper bodies out of a seemingly chaotic background that is

succumbing to the receding – perhaps threatening – vanishing point.

This could be read as optimistic, and the optimism could be related

to the subject’s connection with the photographer, and the viewer.

There is

much more that could be said about the aesthetics of this quite

ordinary shot. For instance, the cheap, single-point, flashbulb

lighting creates shadows at several points of the picture’s depth,

which tends to spray pitch-dark graphic weight along diverging lines

defined by the single-point, reverse-“perspective” of the flash-bulb

light source. These dark divergences add cubistic tension when felt

or perceived in conjunction with the complementary, vanishing-point

system controlled by the lens. In a different graphic register, the

various red objects and shapes seem to reinforce a general tone of

light-redness to the flesh of the couple, and the hair, lips, and

eyelid redness of the woman. And so forth.

Given the

aesthetic density of the shot, is it then to stand accused of

aestheticism, of making poverty and desperation beautiful? Possibly,

but I think not, first, because the aesthetic events in the shot are

patently uncontrived, unarranged, and non-intrusive. One must do

conscious work to see most of the aesthetic elements discussed

above, and even more work to analyse how those elements might be

working metaphorically and emotionally – to see, for example, that

the vanishing point drawing this couple into its third-dimensional,

background vortex is “countered” by the appeal of the direct glance

reaching out of that ineluctable background vector toward the

photographer and toward the viewer. Without such analytical labor as

has been expended here, however, what one sees is a very ordinary

snapshot of a bar scene, arguably clichéd and bathetic –

nevertheless, the effects discussed above may be felt without being

analysed.

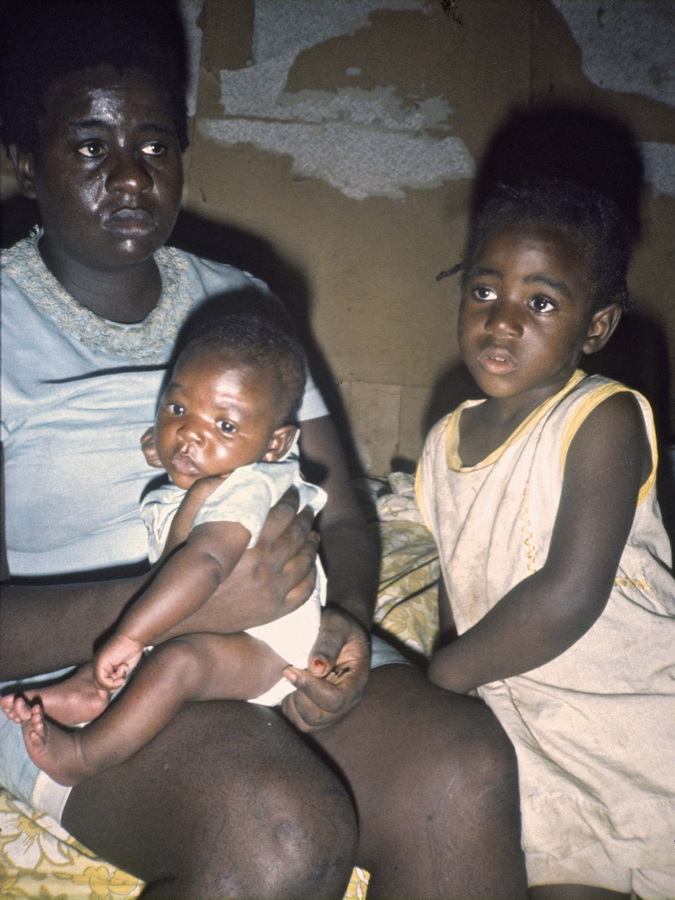

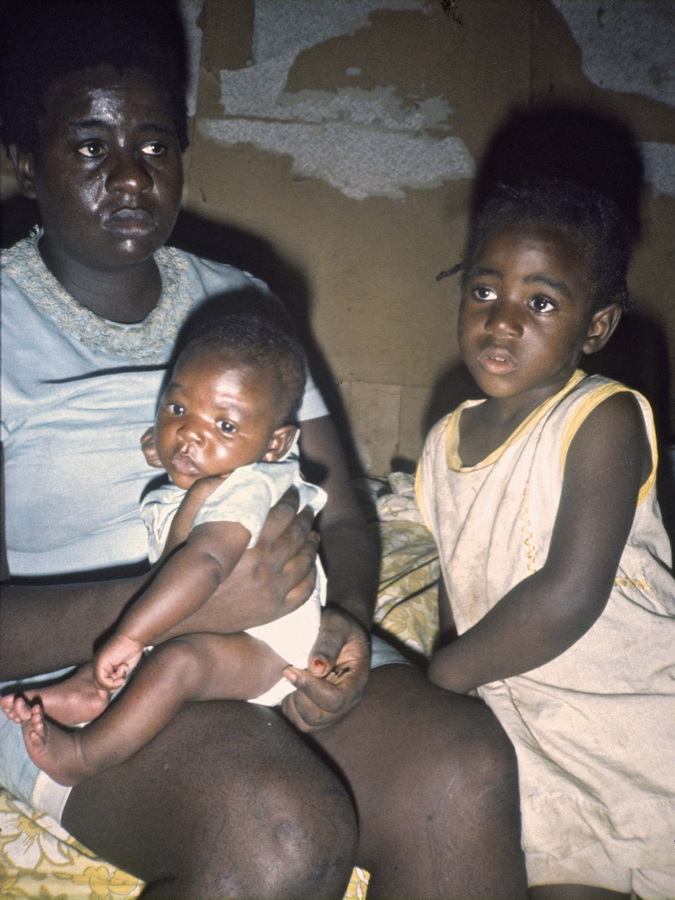

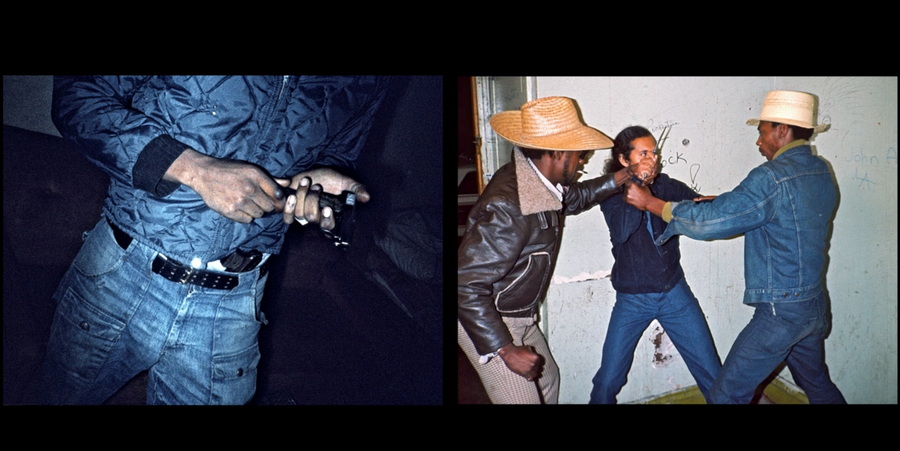

Below is an

even less prepossessing picture, an oblique side-angle, oblique

high-angle medium shot.

This must be

one of the most amateurish shots in Holdt’s project, but, there is

again another way to see its amateurism. If one considers the

expressionistic effect of the single-source lighting – the

flashbulb’s shadows as uncanny distortions of the bodies, the

uncertainty in the eyes of the subjects, the dynamics of facial

expressions and lighting contrasts, the abstract-expressionistic

forms on the wall behind and above these people – this shot again

can become a powerful, even sublime, aesthetic experience. Something

terrible but undefined and alarmingly other-dimensional is happening

to these people; they know it, the photographer captures it, and we

can sense it.

Again, all

three of these shots are aesthetically powerful, but unaestheticised

in the sense that Jafa is concerned about in relation to Eggleston.

Eggleston’s work is painterly. Holdt seems in no way to be

consciously producing beauty, but somehow he is producing, in

virtually every shot, aesthetic sublimity in the Kantian sense –

i.e., a visually stylised sense of overpowering dread that is

inherent in the content and expressed in its forms.

We have seen

how the sublime effects may be created in these shots, but how might

these accomplishments be related to money?

Considering

the last example first, a representation of the “terrible but

undefined” thing that is happening to these people might also be

produced by a highly paid, better-equipped, better-trained

photographer than Jacob Holdt, such as Eggleston, or another

photographer of the South that Jafa mentions, Birney Imes. However,

as Jafa directly implies, pictures such as Holdt’s would be anathema

to such an artist. Even if they wanted to, it would be hard for a

professional photographer to duplicate the quality of the focus in

the shot above – it is not really “soft” focus, and not an

adjusted-focus effect, but rather a product of inadequate light for

the modest quality of the lens. The flash effect that is providing

all the necessary light would be assiduously avoided by a

photographer equipped with a better lens, a multi-point lighting

setup, and the training and skills that would allow the unobtrusive

and invisible handling of those capital assets. Such a photographer

or cinematographer could hardly even imagine such a picture, much

less as a desired objective, nor would any well-paying magazine or

film producer – such as National

Geographic or

CBS, or Random House or Secker and Warburg (publishers of some of

Eggleston’s books), nor even the committed socio-political work of

Magnum Photos – likely pay for such a picture. Such venues, and

virtually any venue investing significant money in such image

content, would expect to see their investments returned in profits,

and would feel the need to see conscious, identifiable aesthetic

value – some perceptible beauty – added to the content of the

images. That

is part of what well-capitalised media mean when they demand minimum

technical standards, and they use their capital to produce work

whose standards only capital can meet. By definition, the picture of

the mother and two children under discussion here is sub-standard in

that discourse, and thus money is very relevant to the production of

such an image.

The same can

be said for the other two images above – that is, that, in the more

capitalised discourses of film, they are all technically

sub-standard. As a consequence of the images’ poor fit within the

better-capitalised systems, the aesthetically high-quality

characteristics of the images that are identified in my analysis

above are perhaps not readily recognizable. Analytical labor is

required in order to demonstrate those aesthetic qualities, a

characteristic not sought by well-capitalised film producers. Such

analytic labour was necessary for every scene in every film

discussed in my two books on Oscar Micheaux; and prior to that

particular labour, Micheaux’s work had been considered by most

critics as important only for its content, not for its aesthetic

power and originality.

It may be, then, that only a poor cinema can

deploy many of the particular aesthetic effects analysed in the

images above, effects that avoid traditional beauty but reach an

aesthetically rich sublimity apparently dependent on financial

poverty. Jafa implies as much in his questions to Holdt in the

interview mentioned above, where Jafa also says: “In my own

particular upbringing in the Delta, which is[,] outside of the

Appalachians[,] in the poorest region in America, I feel like

poverty was more defining than culture, so to speak, or even race.

The culture grows out of the poverty, or is inflected or deflected

or shaped by the poverty.”

Editing

So far, I

have been discussing film stills that might as well be – in fact are

– also in a photography book. They are, however, also the visual

elements in one of the most powerful films I’ve ever seen, which is

the object of this essay. The primary difference between book and

film is temporal editing. Virtually every edit in American

Pictures is

efficient and discernibly relevant to the discursive vector. Many

edits are worthy of special comment for their skill, and some are

utterly brilliant. For example, within the first couple of minutes

of the version of Part I that is presently available for streaming

on Holdt’s website, one

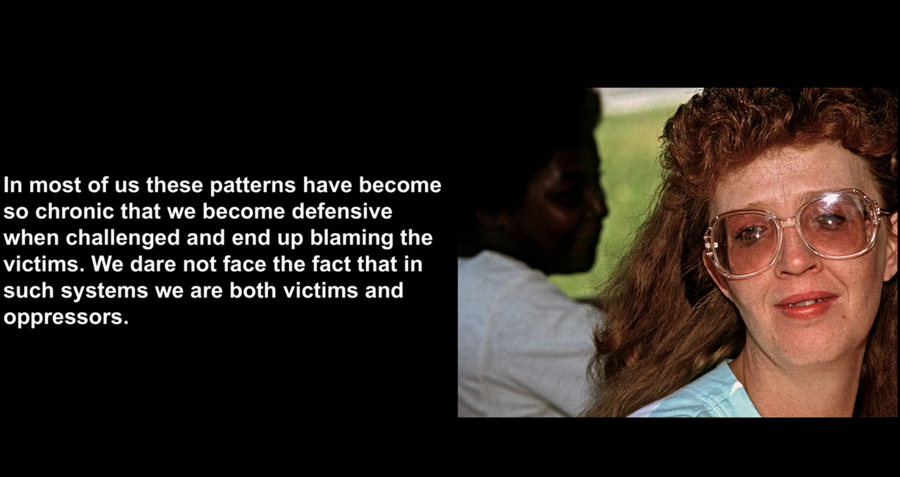

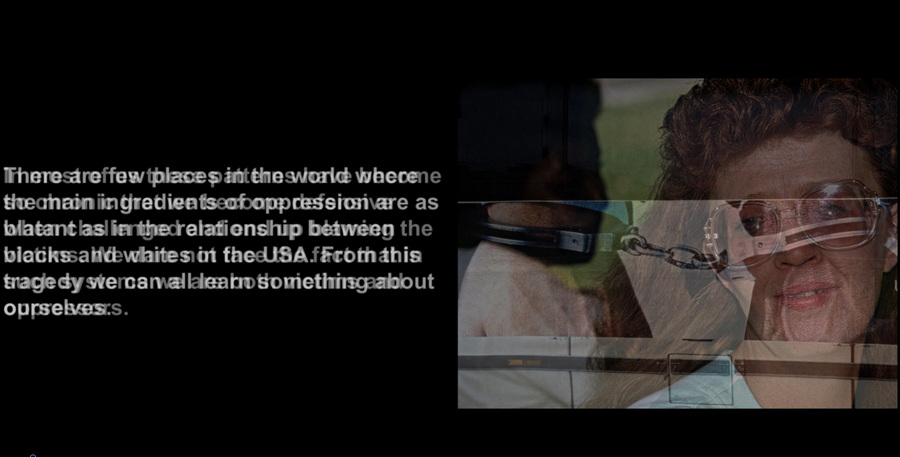

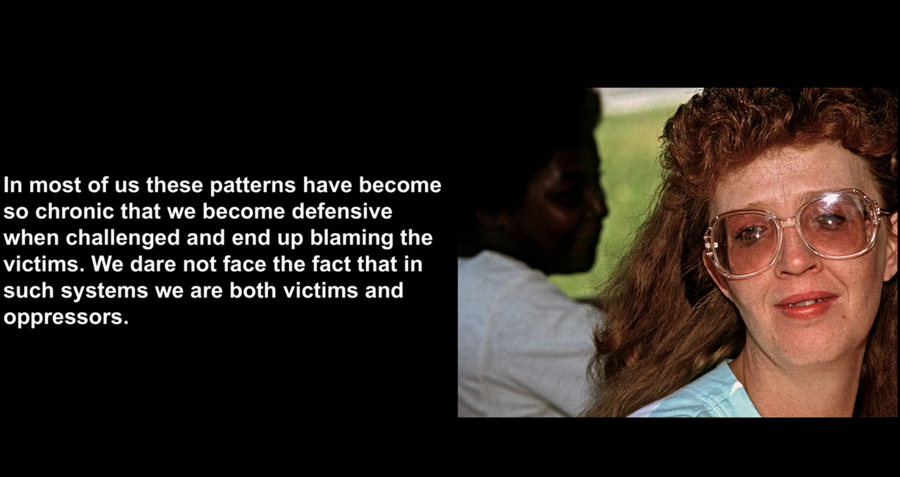

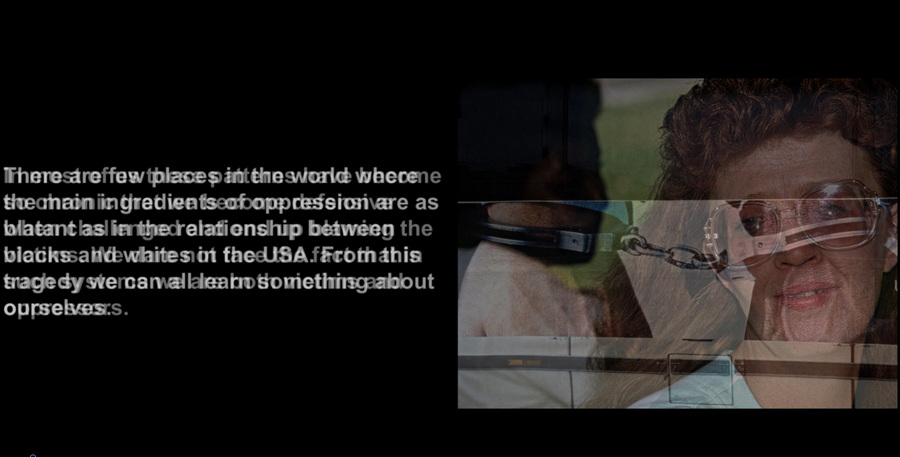

finds an image of a white woman in the foreground and a black woman

in the background.

Before the

next edit occurs, one can hardly help noticing that the two women, though in the

same frame, are treated differently by the shot. The white woman is in the

foreground, body and face toward the camera, looking up and only slightly off

the camera’s axis of orientation—she is in classic suture position, seemingly

ready for a reverse angle edit along the axis of the shot; the black woman,

however, is in the background, body turned away from the camera, face looking

slightly down and almost ninety degrees off the axis of the shot. The white

woman is in classic position, seemingly ready for a reverse-shot to any

pro-filmic interlocutor that might suture the white woman with the eavesdropping

viewer. The black woman is a more distant object in every way, not positioned

for suture with the viewer, but nonetheless observed by the viewer. It is a

disturbing image in its own right, since the emotional appeal of the ingenuous,

outgoing, confident white woman is burdened by the recognition of the pensive,

diffident, more alienated black woman. The next full image is a powerful

statement of that same relationship, but in a different register.

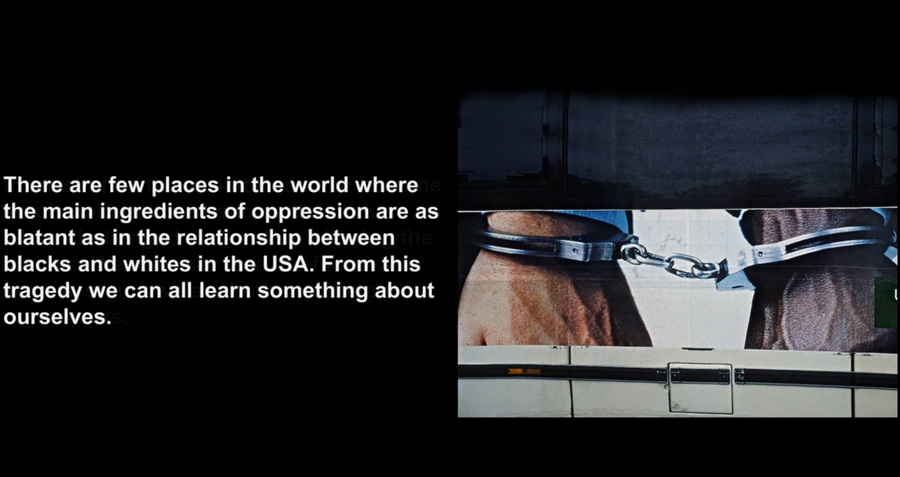

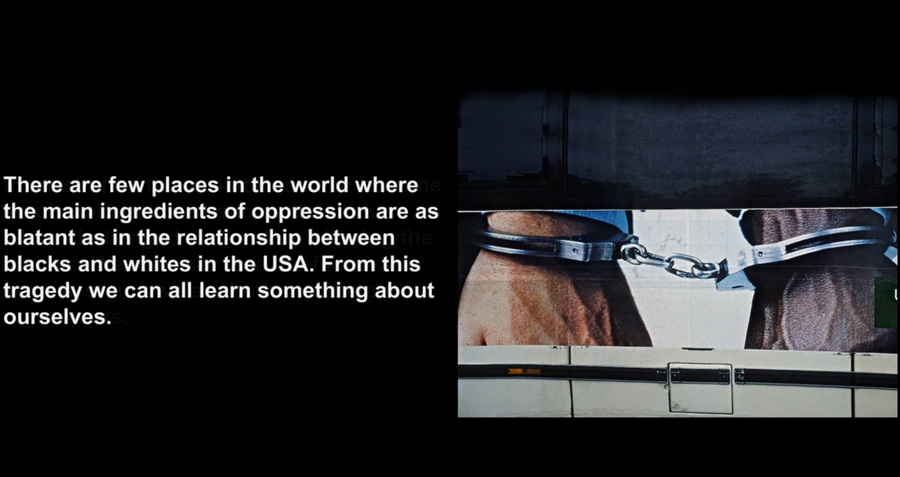

This image of

black and white Americans handcuffed together would be a strong edit if it were

a straight cut from the previous image, and as such quite representative of the

cutting throughout Holdt’s film. It is not a straight cut, however, but a lap

dissolve, which produces not just a good editorial juxtaposition, but a

brilliantly synergistic new image.

During the second or so of the dissolve, the two women are chained together,

like Tony Curtis and Sidney Poitier in The

Defiant Ones (1958).

While Holdt’s intertitles are stating that the patterns of racial distrust are

chronic, and that “we dare not face the fact that in such systems we are both

victims and oppressors,” we see, in the brief image of the dissolve, the chains

of that condition, we see a kind of collar around the black woman’s neck formed

by one of the handcuffs, we see the white woman’s head in some kind of clamp,

and we see that the white woman facing us “dare[s] not face the fact” that she

is both a victim and an oppressor, as the intertitle states. The dissolve

produces an unusually rich metonymic-metaphoric nexus, a nexus that is carried

forward to the next edit, which is another dissolve that uses the handcuffs to

link together black and white.

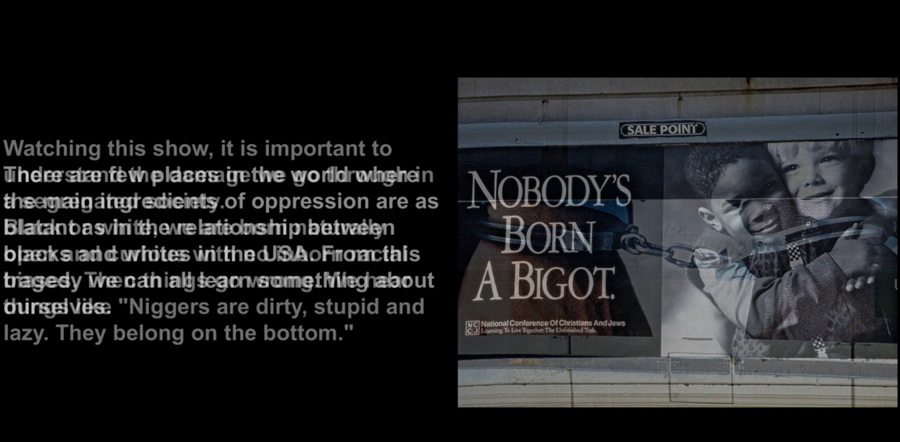

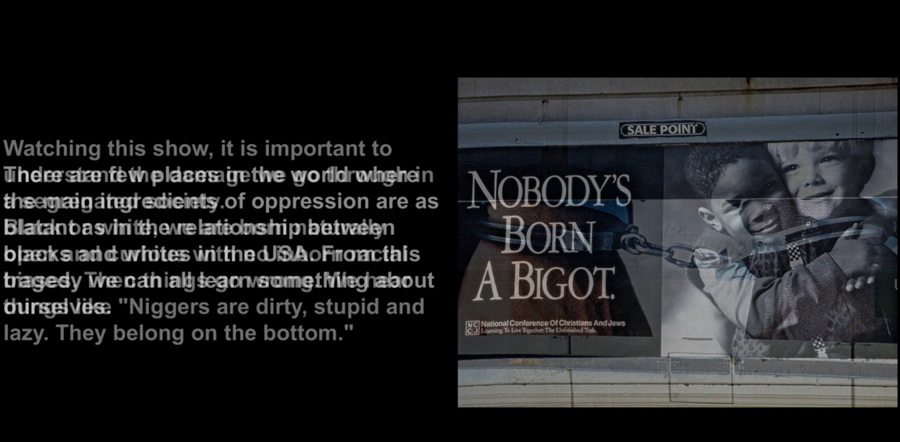

We can see in

the dissolving image that one of the handcuffs is now perfectly aligned with the

necks of two children, collaring them and clamping them together. When the

dissolve is complete, the image changes register again from compulsion and

discipline to affection and magnetism; instead of a steel clamp, a black child’s

arms are hugging a white child’s smiling face to his own, and the

collar/handcuff has dissolved.

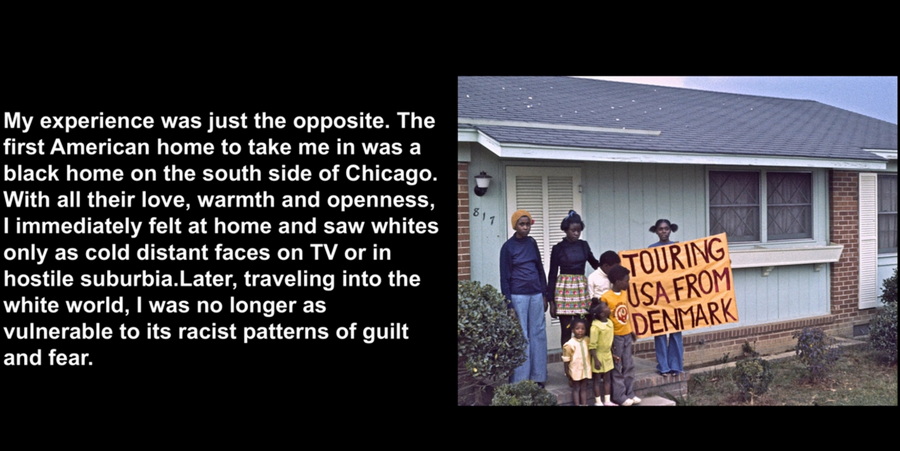

Holdt counts

himself lucky to have landed at this address first, since it

immediately preempted the racist assumptions prevalent in what he

calls the “distant faces on TV or in hostile suburbia.” The

denotative meaning of these visual and verbal juxtapositions is

clear, but the visual snapshot of the black home adds a possible

nuance. If one juxtaposes, in particular, the mainstream white idea

of the location of this home, “the south side of Chicago”, with the

image of the home itself, there is, for many white viewers, a

mismatch. The location “South Side of Chicago” is often rendered in

capital letters, and often connotes “ghetto”. But Holdt’s image

shows, not ghetto poverty, but an average tract house with a porch

light and house numbers like any working-class house in any American

suburb or small town. It is very like the average, white,

middle-class houses I grew up in, and there is no reason why it

should not look like that, except for the part of the mainstream

American mind that may have had difficulty reconciling that image

with a received idea of Chicago’s South Side.

The image of

this family home sets up another edit that, though not necessarily

as brilliant as the handcuffs-and-chains edits discussed previously,

is nonetheless careful and nuanced. In the image above, we notice

the girl holding Holdt’s hitch-hiking sign, “Touring USA from

Denmark”. We have consciously to assimilate that sign because it is

an aberration, since the phrase obviously does not refer to the

person holding the sign. It is the filmmaker’s sign that the girl is

holding. In the intertitles, the filmmaker is also narrating

something directly related to that sign: “Later, traveling into the

white world, I was [because of my initial stay with this black

family] no longer as vulnerable to [the white world’s] racist

patterns of guilt and fear.” That sentence refers directly to the

feel of this picture of an African-American home that is welcoming

to Danish strangers, but it also refers forward to the next picture,

the context of which is white.

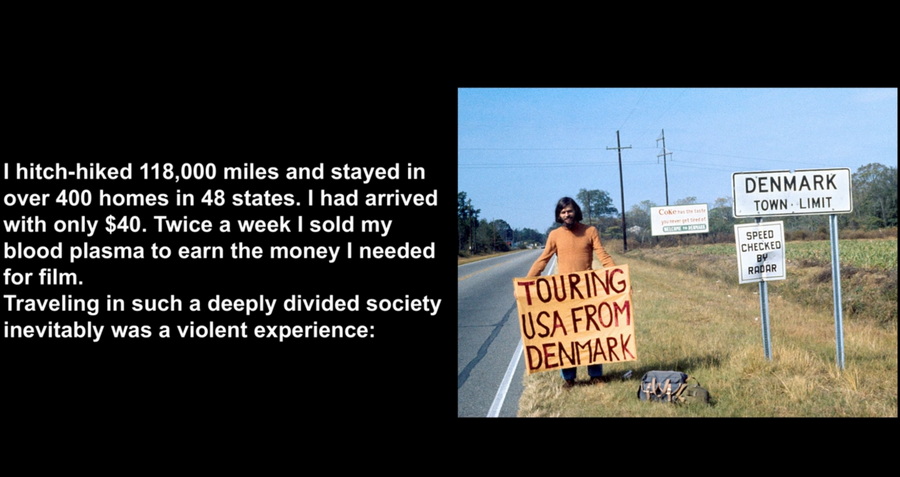

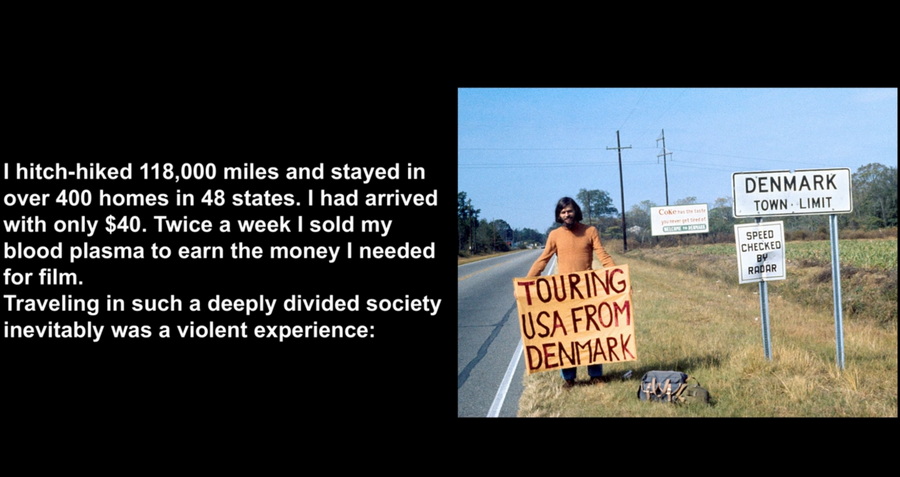

The edit

uses the punctum of the “touring” sign, which rivets the edit by its

placement almost in the same place in the frame as in the preceding

shot, overlapping with itself in the course of the dissolve from the

preceding shot to establish a graphic match between the two shots

across the edit. The “Touring” sign also becomes, within this new

shot, one term of a double punctum, the other term of which is the

“DENMARK TOWN LIMIT” sign. The intertitles accompanying the second

shot continue the reference to Holdt’s move away from the black home

in Chicago and into a racially divided America, referring directly

to the resultant violence. The picture does not yet show that

violence, but Holdt soon takes the viewer through his hair-raising

snapshots that will end this chapter of the film. The proximity of

this image with the violence that follows, and the binding of the

shot with the previous shot of the non-violent, welcoming,

African-American home, lends a nuance of anxiety to the peaceful,

rural, small-town American landscape around Denmark, USA. In fact,

the same “Touring USA” punctum will in a later double-punctum image

show a Ku Klux Klan billboard in the background of small-town

America. The anxiety Holdt associates with small-town America is

exactly complementary to the connotation of security in the South

Side Chicago family’s home, and a reversal of the American

mainstream norm of venerable small-town values.

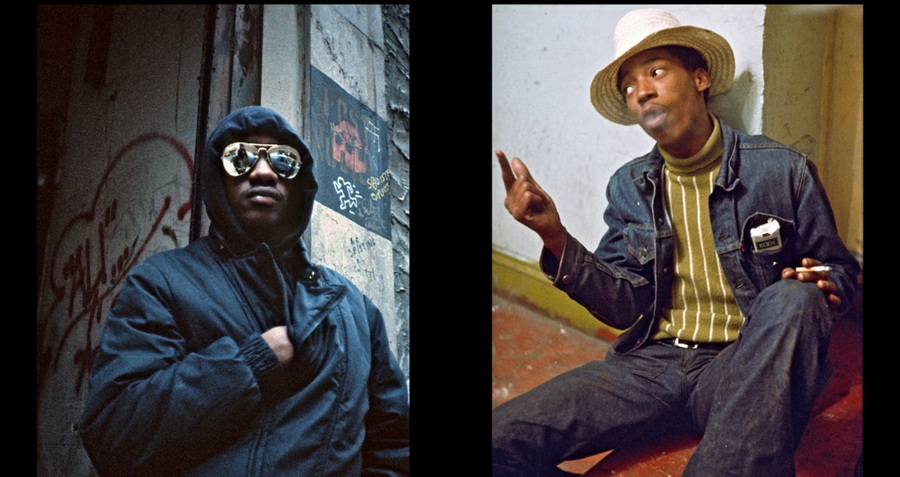

Anxiety,

violence, and insecurity are the dominant issues of the rest of this

chapter of the film. Once Holdt introduces the issue of violence

with the “Touring USA from Denmark” sequence, he accompanies those

ideas with images of places in small-town and urban America that

most Americans would never go.

Reasons why

one would want to avoid such places are recognised by Holdt, and

direct evidence of the danger is shown in Holdt’s documention of

physical violence, including possibly murder, later in this chapter.

But, as the intertitle of the above shot implies, Holdt is committed

to the basic goodness of the people in these places, and his project

is to bring the viewer along.

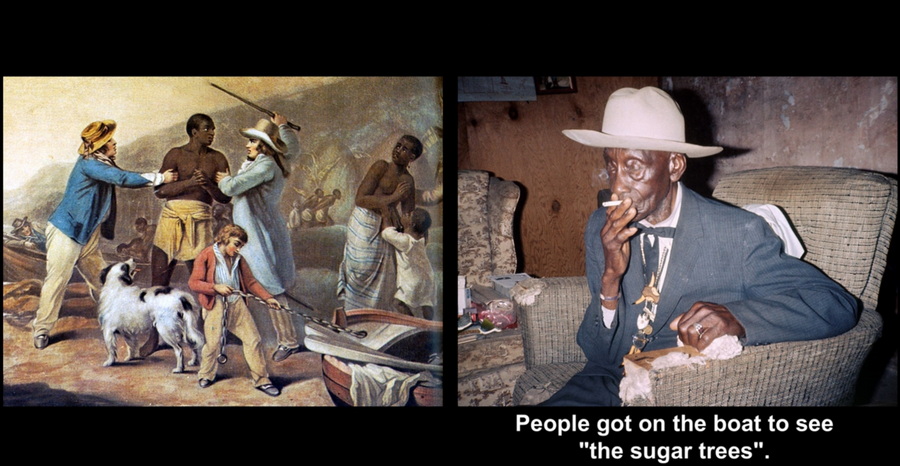

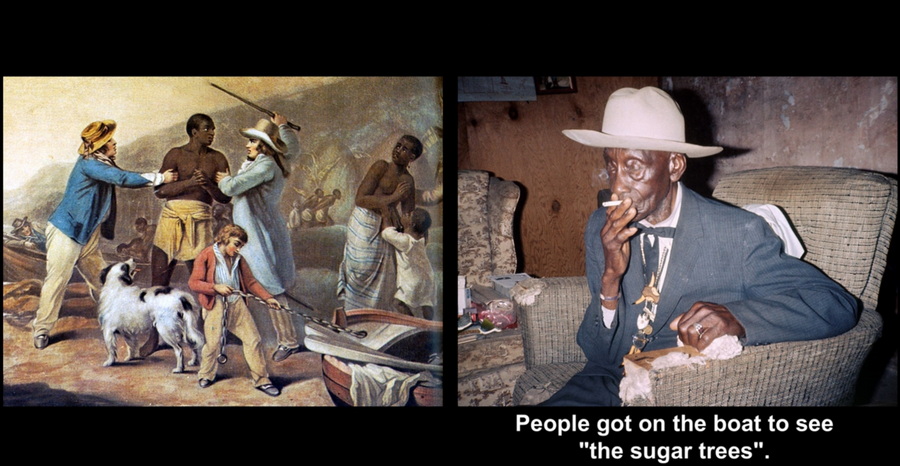

He starts that journey by reviewing the history

of slavery. He constructs the journey as an attraction for the

audience. It is important to mention here that his use of sound, an

important element of film style, is a significant part of the

editing here and a major element of the film journey’s attraction in

general. The film’s first chapter thus far has been accompanied by

sounds representing the creaking hull of a heavy wooden slave ship

rolling on the high seas. When Holdt’s mention of violence occurs

for the first time, an appealing but hauntingly minor-keyed music

begins. When the theme of black anger and violence becomes the main

focus of Holdt’s intertitles, popular black protest music from the

1970s or ‘80s is foregrounded on the soundtrack and its lyrics

become the film’s narration. These editing decisions create a strong

flow that sweeps the audience into territory it might otherwise want

to avoid. This is all occurring during sections of the film where

Holdt is giving the history lesson of slavery and introducing to us

the people who are dangerous, but who are also worthy of basic

trust, as Holdt’s own decades-long journey into their world is meant

to prove. Holdt’s editing, then, does not depend only on the

attractions of “epistephilia” that Bill Nichols has described, but

also on attractions such as sensational visual testimonials and

popular music such as Gil Scott-Heron’s “Whitey on the Moon.”

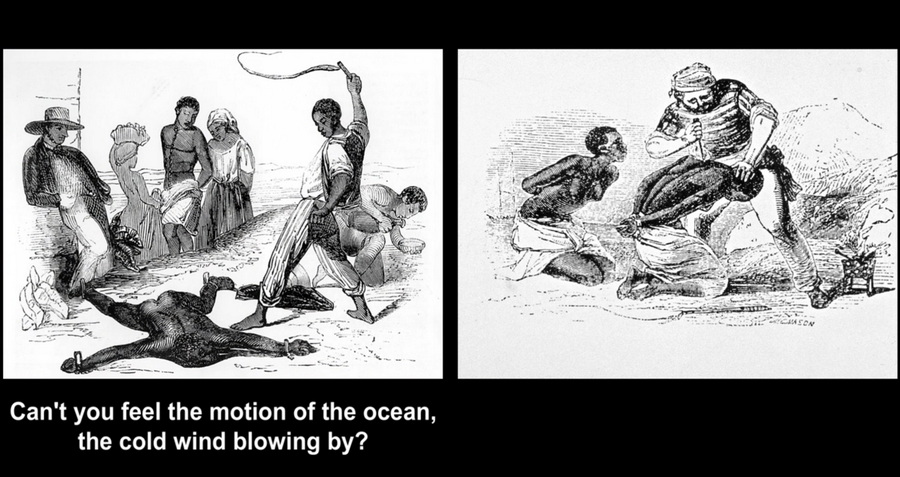

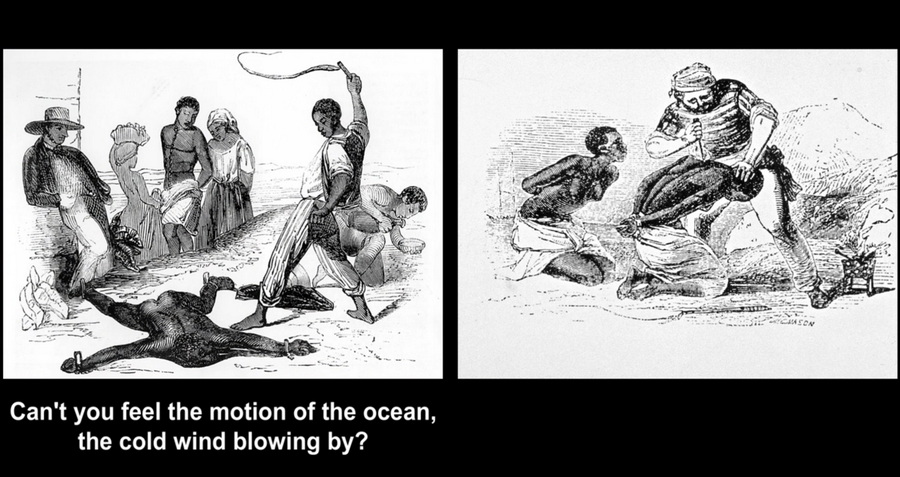

The editing

in the history-of-slavery lesson is extraordinary, as it would need

to be to hold the attention of average viewers, who are not famous

for their interest in history lectures. A good example of the

quality of the editing is the way Holdt ends that lesson. At this

point, he is letting recent Black American pop music about slavery

narrate the lesson, and as the song comes to an end,

eighteenth-century engravings are used to portray the flogging and

branding of slaves, with the lyrics of the pop song reproduced as

titles.

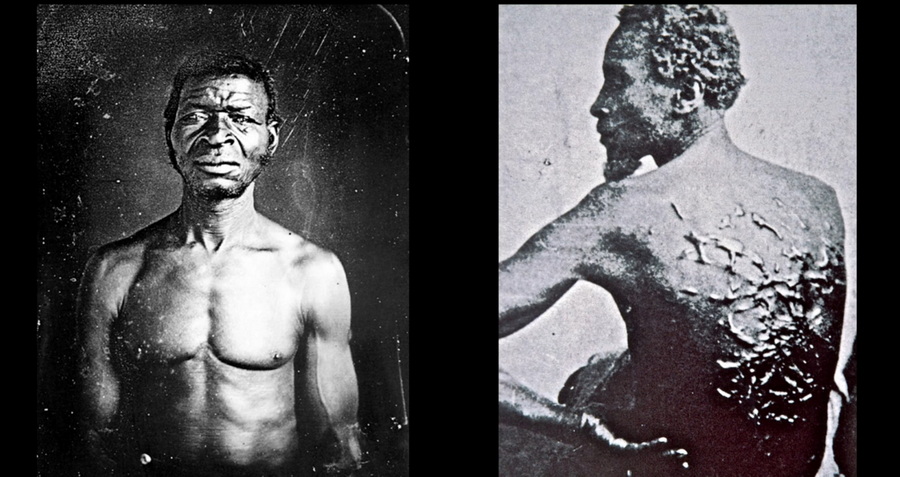

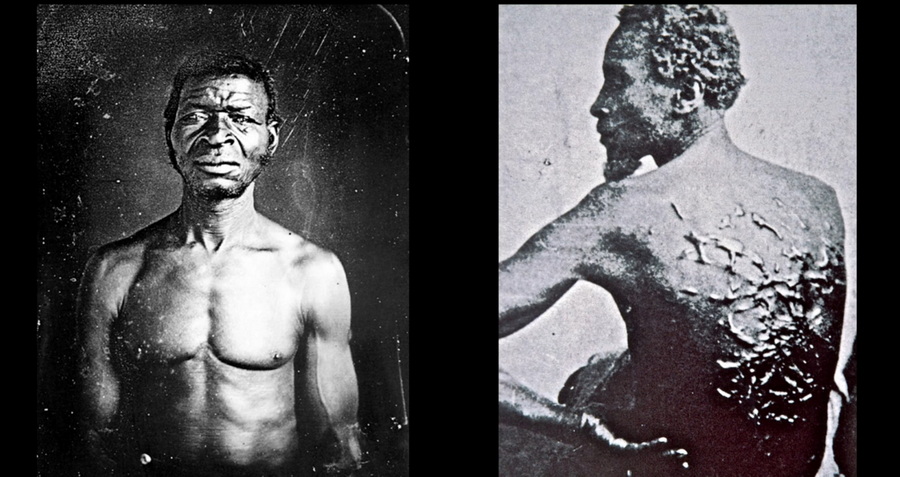

These prints

are followed by nineteenth-century photographic evidence of such flogging and

branding.

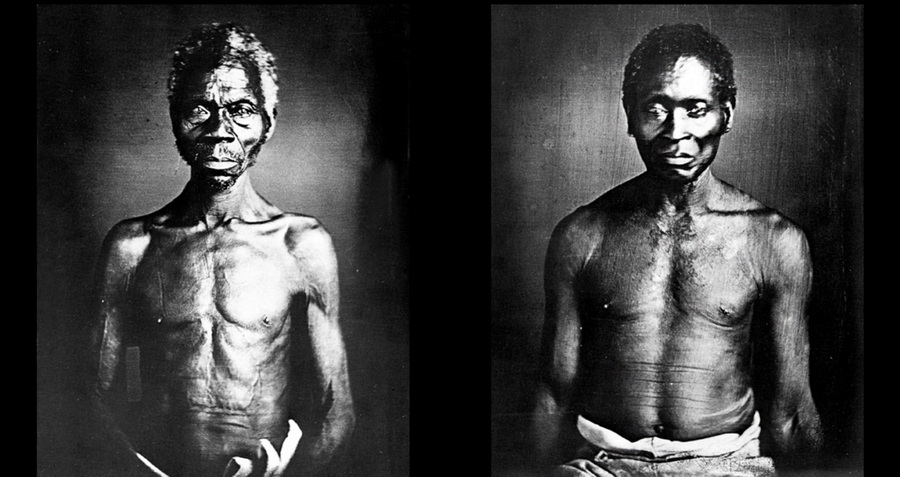

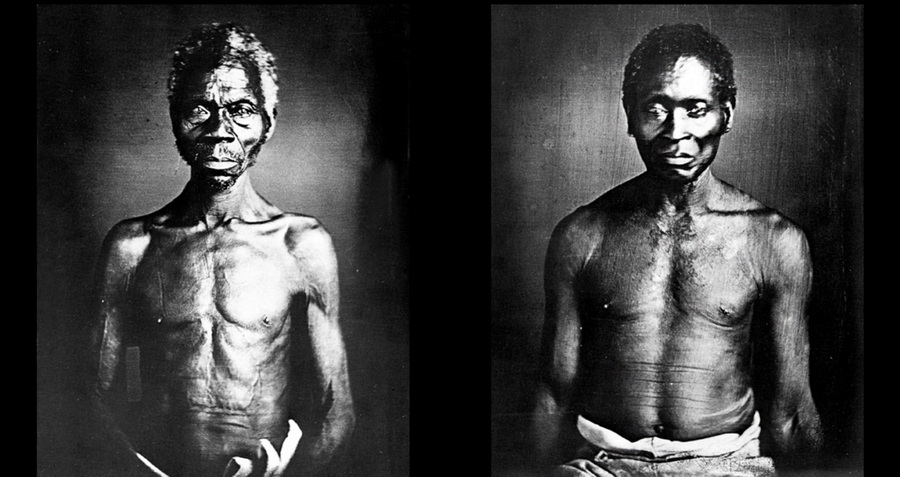

Then occurs

one of the most startling edits in the film, as these eighteenth- and

nineteenth-century documents – seemingly ancient history – are, without missing

a beat, replaced by Jacob Holdt’s own photographs of a “134-year-old former

slave.”

The power of

this move “out of history” and into the present is supported by a

similar edit on the soundtrack, where we hear Holdt’s voice for the

first time in the film, the voice of the person who will be

testifying to the truth of these conditions and of this sort of

audio-visual evidence, the voice of the Virgil who will guide the

audience for the next three or four hours. Holdt then one-ups this

strong sound edit by presenting the voice of the former slave

speaking for himself, which Holdt had recorded at the same time he

took the above images. This living example of America’s past is an

epiphany, the effect of which is magnified by the editing. Those

nineteenth-century, ancient-history images of physically mutilated

slaves come to life, morphing into colour, their tape-recorded

voices telling us their stories “directly”.

Holdt continues the history lesson, returning

to historical images, though now illustrating the testimony of an

“honest-to-goodness” former slave who was “really there” when those

old engravings, prints, and photographs were made.

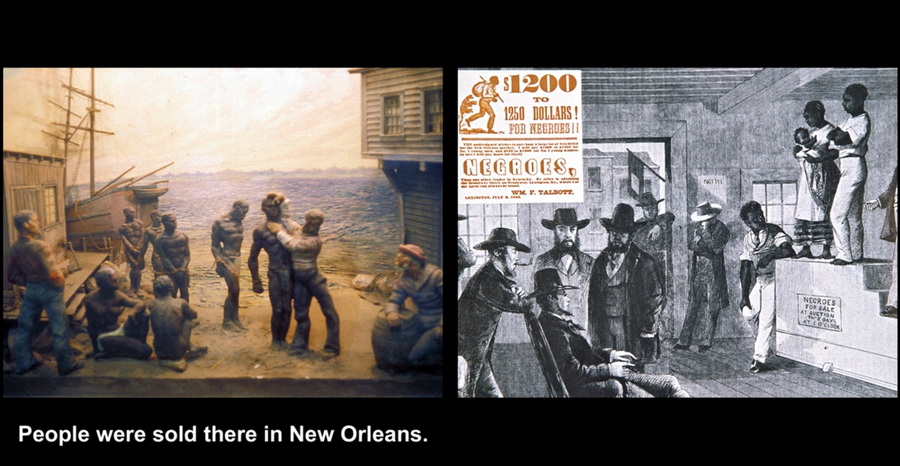

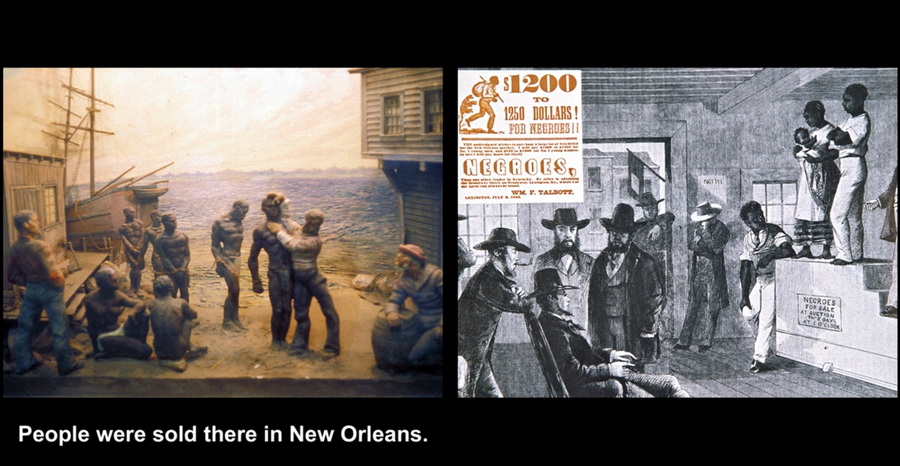

The most

uncannily lifelike of those accompanying images is from a diorama, probably

found by Holdt at a civil rights or history museum somewhere.

In the next

edit, the sculptural forms of the diorama on the left above, and the pedestal on

the right-hand image, are made to rhyme unnervingly with familiar post-slavery

monuments.

Holdt’s edit between these two diptychs of

frightening-vs.-comforting, three-dimensional figures implies that

the aspects of the history of slavery that we keep prominently in

public view are those that some of us – the white monument-funders –

prefer to remember. Holdt’s career-long project has been the

continual creation of a record that remembers differently, and

aspects of Holdt’s style, such as the edit above, contribute to that

differentiation of remembering.

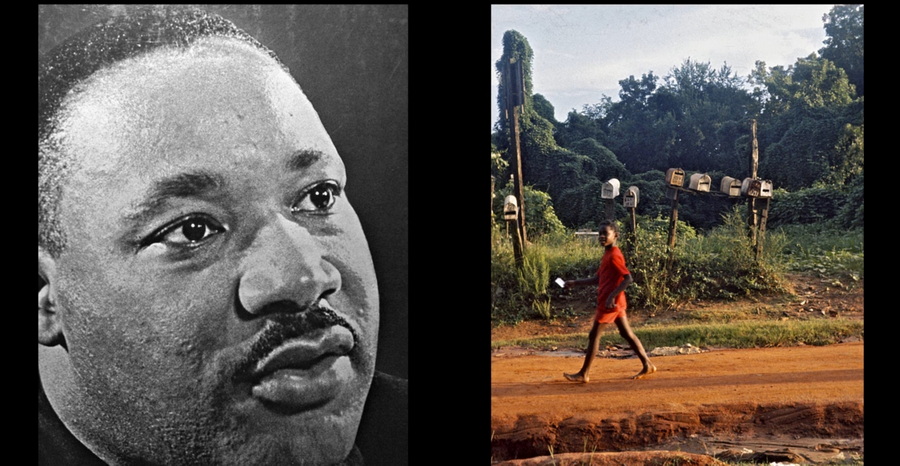

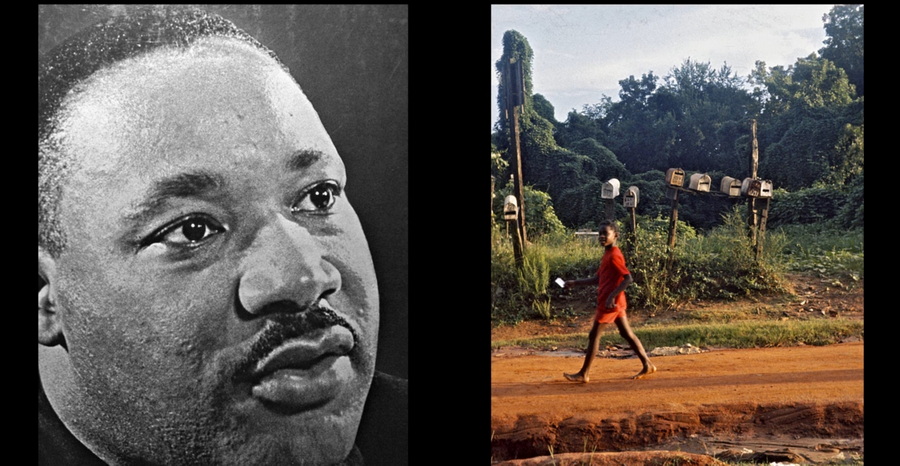

Soon after

this sequence, Holdt continues the images of emancipation with

Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech on the soundtrack,

illustrated by both heroic portraiture and vernacular Holdt

snapshots.

But

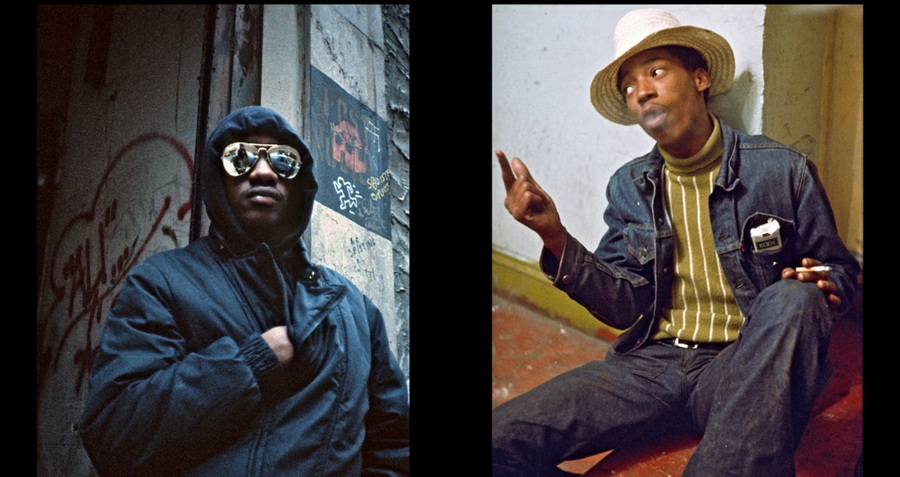

then, to conclude this opening chapter of his film, Holdt returns to the world

of today, decades after King’s speech, where African-Americans are still steeped

in poverty and murderous violence.

It is into

this world, primarily, that he invites the audience to follow him

for the remainder of the film.

Mise en scène

Mise en

scène is

the selection and arrangement of everything in front of the camera,

all the stylistic decisions that do not involve the handling of

camera and film. It includes, in fiction films, choices such as

actors, acting style, blocking, sets, locations, costumes, makeup,

art direction, and lighting. In documentary filmmaking, mise

en scène potentially

includes all of the above, but most generally it includes decisions

about what people and places to film, as well as how to alter and

arrange those people and places before or during the shooting.

Holdt’s mise

en scène can

be characterised is minimally arranged. He typically films people

and places as he finds them. He probably does not ask them to act or

re-enact; he does not use sets nor often alter the locations where

subjects and objects find themselves; his only lighting effects are

primitive flash when available light is inadequate to securing a

basic photographic record. He does not professionalise the interview

situation by constructing a dramatically lighted, talking-head, and

re-enactment aesthetics such as can be found in countless

documentaries like Errol Morris’s The

Thin Blue Line (1988)

or Fog

of War (2003)

or Alex Gibney’s Taxi

to the Dark Side (2007).

Nor does he schedule his filming of landscapes and locations to

utilise the sublime early-morning and late-afternoon light to add

aesthetic appeal or gratuitous sublimity, as so many documentaries

do.

He does,

however, intervene in some important ways in the situations that he

documents. He directs people to stand or sit for a picture, like the

family in front of their South Side Chicago home; he asks people to

take pictures of him in certain positions, such as standing beside

the “DENMARK TOWN LIMIT” sign. There are other such interventions,

but they are both transparent and minimal. Holdt’s people and places

are as ordinary as those in much of the mise

en scène on

YouTube. Also, the inclusion of these interventions is intrinsic to

the first-person nature of the project; Holdt, as filmmaker,

narrator, and storyteller, is always meant to be part of – and

active agent within – the story told. It would be more manipulative,

intrusive, and directorial of him to excise himself from the mise

en scène,

as is standard procedure in most documentaries.

Holdt’s

minimal treatment of the reality in front of his camera and tape

recorder, combined with the unprecedented range of his choices of

what sorts of people and places to film, is probably the most

rhetorically and aesthetically powerful aspect of his project. It is

the aspect of Holdt’s style that produces the effect of intimacy

that Jafa finds unique in Holdt’s work. One might be tempted to

think that Holdt’s minimalist realism, a kind of cinéma

vérité,

is the easiest of the stylistic elements available to him, since it

takes professional training, visual literacy, and skills to handle mise

en scène the

polished way that Alex Gibney and Errol Morris handle it. But in

fact Holdt’s way is not easy and its value is proportional to its

difficulty. The level of difficulty can be assessed in terms of

time, suffering, and risk. The material that Holdt presents is

almost-literally unbelievable – after all, he started the project

when his family and friends in Denmark refused to believe what he

was writing home about, and they sent him a cheap camera to prove

his claims. His incredible images and events, including the

occasional show stoppers that all documentarians hope for –

including his close encounters with inaccessible figures such as

1970s slaves in America’s sugar plantations; pre-Civil War former

slaves, all of whom one had assumed to be long dead; presidents’

daughters such as Julie Nixon; FBI directors such as Clarence Kelly;

famous Rockefellers and Kennedys; FBI informants and presidential

attempted-assassins such as Sara Jane Moore (who is still in prison

today); black-power martyrs such as Popeye Jackson – are available

to Holdt’s film because of the time and risk invested in the

project, and, in fact, as Holdt tells Jafa, because of his own

poverty as a filmmaker.

Human Scale Aesthetics

The levels

of time and risk invested by Holdt are simply too high for most

filmmakers to consider, and it is partly the viewer’s recognition of

the time and risk taken to deliver this material that makes the

experience of the film so affecting. But there is an additional mise

en scène effect

that adds value beyond the viewer’s recognition of the time and

risk. The unbelievable material – such as the plantation-like,

contemporary slave camps and the people who still eat dirt, and the

epiphanic close encounters with power, celebrity, and danger – are

human-scale. They emerge out of the life experience of a person much

like the average viewer, a person who has little wealth, no

professional film skills, no special access to power and celebrity,

and whose prior experience of the dangerous realities inherent in

the realms of racism, poverty, and crime is limited to fiction and

more-or-less distanced, objective documentary. The average viewer’s

documentary knowledge is derived from the institutions of

documentary – the evening news, National Geographic, the History

Channel, Frontline, the classical film-studies canon, and the like.

These days,

an increasing amount of the average viewer’s documentary experience

comes from new institutions like YouTube and similar platforms, but

that is my point. Holdt’s project foreshadows that YouTube world of

publicly accessible films by ordinary people. YouTube is the world

from which the somewhat younger Jafa draws for his own powerful

work. Holdt’s earlier œuvre has the authority of those works in that

it is embedded in ordinary lives, including Holdt’s own drop-out

vagabonding. While it falls short of perfect authorial authenticity

by not being

a documentary by the

people it portrays in that vagabonding, it rises well above the

average YouTube work by its unprecedented investment of time

(virtually an entire life), of suffering (Holdt was often

miserable), and literally the risk of life and limb.

This

investment of human-scale labour and bodily and psychic risk-taking

is what makes Holdt’s mise

en scène,

and his entire resulting aesthetic, significant. The effect of a

professional, capitalised-scale documentary film that attempted to

do what Holdt has done would be different; the more capital value –

such as camera quality, production and post-production skills – that

one might add to the project would proportionally alienate the mise

en scène from

the people, places, and situations portrayed, and that alienation

would be visible and audible to the viewer.

Holdt’s film

has the feel of an unusually careful and thoughtful home movie. And

since almost anyone can make a home movie today, Holdt’s mise

en scène contributes

to a democratic aesthetic. Michael Moore’s, Errol Morris’s, and Alex

Gibney’s movies do not look homemade; few viewers feel when watching

such films that they look like home movies that they could have made

themselves. Thus, Moore’s, Morris’s, and Gibney’s films, important

as they are to the democratic process, are less democratically

produced, and thus less fundamentally democratic, than Holdt’s. This

suggests the question as to which aesthetic is more effective,

Holdt’s or Gibney’s, which is a good question but that is not the

issue here. My point is that if one is looking for aesthetics that

can produce films as powerful and affecting as any in film history,

and that at the same time are truly democratic, Holdt’s project is

an instructive model, one that cannot be matched by better financed,

more-widely distributed films. There is apparently an art of cinema,

which I am calling Poor Cinema, that is not only beyond the reach of

money, but is averse to money, and it can be more sophisticated in

its making, and more affecting in its beholding, than most

filmmakers and audiences are yet aware of.

The Poor-Cinema Project

To begin

this essay, I mentioned that Arthur Jafa had praised the uniqueness

of the content and style of Holdt’s images, and had admired the

authenticity, effectiveness, and integrity of those pictures. Jafa

compared Holdt’s images favorably to similar images by artists

firmly in the canon, such as William Eggleston, and I have compared

Holdt’s filmmaking to canonical filmmakers such as Michael Moore. In

search of general principles to explain the relative value of

Holdt’s work, this essay has explored one aspect of the images and

filmmaking that Jafa and I have admired – their style. It appears

significant that Holdt’s style grew directly from his working

conditions.

In the

larger-scale book project on poor cinema, the unpublished chapters

that follow this essay dig more deeply into the specific filmic

content that Holdt’s methods produced, including specific critical

targets, and issues of critical integrity – specifically in relation

to money. The larger poor-cinema project includes my two books on

Oscar Micheaux, plus a manuscript on Terminator

3; Rise of the Machines (Jonathan

Mostow, 2003) as an example of a critically ambitious rich cinema.

The larger hope for these essays is to encourage more attention to

under-the-radar modes of relatively inexpensive filmmaking, wherever

worthy examples are found. Poor cinema is an acquired taste, but a

taste worth acquiring.

Endnotes

Copyright © 2010

AMERICAN PICTURES |

|