Book 15, pages 256-258

One day I saw in the New York times a picture of Mayor Lindsay presenting a

bouquet of flowers to a "heroic" police officer in a hospital bed. It said that

he had been shot down while "entering an apartment." I decided to find

out what was actually behind this incident and nosed around the Bronx for

several days to find the relatives and the apartment where it all took place.

Little by little I found out what had happened. James and Barbara were a young

black couple who lived in the worst neighborhood in the U.S.A. around Fox

Street in the South Bronx. One day they heard burglars on the roof and called

the police. Two plain-clothes officers arrived at the apartment and kicked in

the door without knocking. James thought it was the burglars who were breaking

in, and he shot at the door, but was then himself killed by the police. Barbara

ran screaming into the neighbor's apartment. When I went to the 41st Precinct

police station they confirmed the story and admitted that "there had been a

little mistake," but James of course "was asking for it, being in possession

of an unregistered gun."

I was by now so used to this kind of American logic that I did not feel any

particular indignation toward the officer. I just felt that he was wrong. Since

I had spent so much time finding out the facts of the case. I might as well go

to the funeral, too. I rushed around town trying to borrow a nice shirt and

arrived at the funeral home in the morning about an hour before the services. I

took some pictures of James in the coffin. He was very handsome. I admired the

fine job the undertaker had done with plastic to plug up the bullet holes.

Black undertakers are sheer artists in this field; even people who have had

their eyes torn out they can get to look perfectly normal. Since black bodies

arrive in all possible colors and conditions, they use almost the entire color

spectrum in plastic materials. James did not make any particular impression on

me; I had already seen so many young black corpses. The only thing I wondered

about was that there wasn't any floral wreath from the police. I waited about

an hour, which was to be the last normal hour that day. Not more than ten

people came to the funeral, all of them surprised at seeing a white man there.

A young guy whispered to me that he thought it was a little unbecoming for a

white man to he present at this particular funeral. Then suddenly I heard

terrible screams from the front hall and saw three men bringing Barbara in. Her

legs were dragging along the floor. She was incapable of walking. I could not

see her face, but she was a tall, beautiful, light-skinned young woman. Her screams made me shudder. Never before had I heard such

excruciating and pain-filled screams. When she reached the coffin, it became

unbearable. It was the first and only time in America I was unable to

photograph. I had taken pictures with tears running down my cheeks, but had

always kept myself at such a great distance from the suffering that I was able

to record it. When Barbara came up to the coffin, she threw herself down into

it. She lay on top of James and screamed so it cut through marrow and bone. I

could only make out the words, "James, wake up, wake up!" again and again. The

others tried to pull her away, but Barbara didn't notice anything but James. I

was at this point completely convinced that James would rise up in the coffin.

I have seen much suffering in America, but I have often perceived in the midst

of the suffering a certain hypocrisy or even shallowness, which enabled me to

distance myself from it. Barbara knocked my feet completely out from under me.

Everything began to spin before my eyes. It must have been at that point that I

suddenly rushed weeping out of' the funeral home. I ran for blocks just to get

away. My crying was completely uncontrollable. I staggered down through Simpson

and Prospect Streets, where nine out of ten die an unnatural death. Robbers and

the usual street criminals stood in the doorways, but I just staggered on

without noticing them, stumbling over garbage cans and broken bottles. It was a

wonder that no one mugged me, but they must have thought I had just been

mugged.

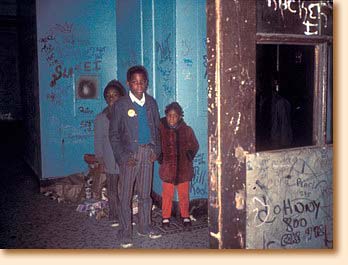

When I got to James' and Barbara's apartment building, still crying, I asked

some children if there was anyone up in the apartment "of the man who was shot

the other day." They asked if I didn't mean the man who was shot in the

building across the street last night. No, it was in this building, I said. But

they had not heard that anyone had been shot in their building. They lived on

the third floor and James and Barbara lived on the sixth floor. I went up to

the apartment, which now stood empty.

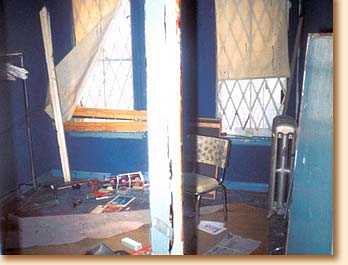

Robbers had already ransacked it, and

there were only bits of paper and small things scattered around on the floor.

The emptiness of the apartment made me sob even harder. There were bullet holes

all over in the living room wall where James had been sitting, but there were

only two in the door which the police had kicked open.

There were three locks

on the door like everywhere in New York, as well as a thick iron bar set fast

in the floor - a safety precaution the police themselves recommend that people use to avoid having their doors sprung open by criminals. James

and Barbara had been so scared of criminals that they had put double steel bars

on their windows although it was six stories up and there was no fire escape

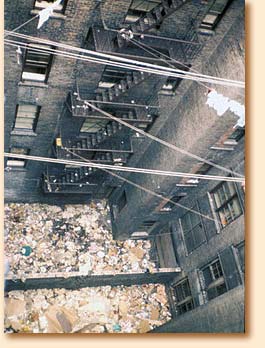

outside. Down in the courtyard there was a three-foot pile of garbage people

had thrown out of their windows.

Here James and Barbara had lived since they

were sixteen with their now four-year-old daughter. After a couple of'

hours I

ventured out of the apartment. I had cried so much that I had a splitting

headache, and all the way into Manhattan the weeping kept coming back in waves.

When I came to a movie theater on the West Side, I wandered in without really

knowing what I was doing. It was at that time that movies directed by blacks

were being produced for the first time in history. The film was called

"Sounder" and was about a poor family in Louisiana in the 1930's. There was an

overwhelming sense of love and togetherness in the family, but in the end the

father was taken away by the white authorities and sent to a work camp for

having stolen a piece of meat. The film was made in Hollywood and romanticized

the poverty; after several years in a work camp, the father came back to the

family, so the film would have a happy ending.

This wasn't the kind of poverty I had met up with in the South. The only time I

cried in the movie was when I saw things that reminded me all too much of James

and Barbara. Afterward I wandered over in the direction of Broadway. An old

black woman whom I had stayed with in the North Bronx the night before had

given me ten dollars so I could get some nice clothes for the funeral. She had

at first not trusted me and had spent several hours calling various police

stations asking them what was the idea of sending an undercover cop to her

house. But when after half a day she had assured herself that I was not a

police agent, she was so happy that she gave me the ten dollars, and I had to

promise to come stay with her again, and she telephoned to Alaska so I could

talk with her daughter who lived up there. Now I still had a little money left

over and went in my strange state of mind straight into another movie theater

on Broadway and saw "Farewell, Uncle Tom." It was a harrowing film about

slavery. It was made by non-Americans (in Italy), so it didn't romanticize

slavery. You saw how the slaves were sold at auction, the instruments of torture that were used, and you saw

how men were sold away from their wives and children. It was frightful. How

could all this have been allowed to happen only a hundred years ago? At some

points in the film I almost threw up. I looked around the cinema repeatedly, as

I was afraid that there would be blacks in there, but there were only two

people in the whole theater besides me. When I got outside, there was a young

black guy hanging around with sunglasses on. I stood for a long time looking

him in the eyes, and I couldn't understand why he didn't knock me down.

For

days afterward I was a wreck. I will never forget that day. It stands

completely blank in my diary. A whole year went by before I pulled myself

together and sought Barbara out. But when I came to the kitchen at the

veterans' hospital where she worked, an old black woman was sent out to talk to

me. She told me that she was Barbara's guardian, since Barbara had not been

normal since the funeral. She had become very withdrawn and never spoke any

more. I asked her what Barbara had been like before James' death. She went into

deep thought for a moment and then told me with tears in her eyes about the

four years when James and Barbara had worked together there in the kitchen.

They had always been happy, singing, and a real joy to the kitchen personnel.

They had never missed a day of work, always came in together and always left

together at the end of the day. But she wouldn't let me see Barbara, for

Barbara did not wish to see anyone.

Another year went by before I sent a letter to Barbara from somewhere in the

South. I assumed that by now Barbara had gotten over her husband's murder. When

I again went to the kitchen, the same elderly woman met me. It was as if time

had not passed at all, and we just continued where we left off. She sighed

deeply and looked into my eyes. "Barbara has gone insane," she said.

Barbara kept coming up in my thoughts wherever I traveled. But another event

came to make just as strong an impression on me. Somewhere in Florida an

unhappy white woman had climbed up a water tower and stood on the edge, about

to commit suicide. But she couldn't make herself jump. It was in a ghetto area

and a large crowd of people, most of them black, gathered at the foot of the

tower. The police and fire department were trying to persuade the woman not to

jump, while the crowd shouted for her to jump. I was totally unable to

comprehend it. I shouted as loud as I could: "Stop it, stop it, please, let the

poor woman live." But their shouts grew louder. It was the worst and most

sickening mass hysteria I had ever experienced. Then suddenly it hit me that

the screams sounded like Barbara's on that unforgettable morning. I started

getting weak in the knees and rushed off, just as fast as at the funeral home.

In five years I will try to contact Barbara once more. I must see her face

again some day!

Summary of letters

Copyright © 2005 AMERICAN PICTURES; All rights reserved.